Home

Español

Español

Se rumorea que… Centro de refugiados del pueblo gitano,…

Un rumor puede ser verdadero o falso. En cualquier caso, conforme

se extiende, opera en la imaginación pública y crea pautas de pensamiento

y de comportamiento. Se rumorea que… Centro de refugiados

del pueblo gitano es una intervención propuesta (aunque nunca realizada)

para el espacio urbano de la ciudad de Hull que continúa con el

duradero compromiso de Andújar con la población gitana en Europa

y contra la estigmatización xenófoba que encasilla a esta minoría

como «los otros». A través del concepto de rumor y «utilizando la

ciudad como medio», la intervención aspira a crear una imagen simulada

de una realidad diferente en la que la discriminación desenfrenada

hacia los gitanos se sustituye por la política abierta de «una

comunidad basada en la solidaridad». El rumor consistía en que se

estaba construyendo en Hull el mayor centro de refugiados para gitanos

de Europa. TTTP difundiría el rumor a través de los medios de

comunicación y una enorme valla publicitaria colocada en el espacio

urbano. El rumor era falso (una simulación) pero apuntaba a una

realidad existente en Hull y a una posibilidad igualmente existente

de cambiar esta realidad. Tal y como se dice en el material escrito

que debía acompañar la intervención, «la simulación crea emociones

a las que la realidad no llega». Además de las vallas publicitarias, la

intervención constaba de una serie de terminales de ordenador públicos

colocados en diferentes puntos de Hull, donde los ciudadanos

podían participar, contestando a un amplio cuestionario, en lo que

se presentaba como un proyecto de investigación social. El cuestionario,

un formato que TTTP utilizaba en diferentes proyectos en

aquel momento, se centraba en el racismo y en la percepción de «los

otros», en particular, los gitanos. La intervención, como tal, pretendía

hacer hincapié en la necesidad de reconocer a la minoría gitana

y permitirles integrarse en la sociedad sin tener que abandonar su

especificidad cultural.

English

English

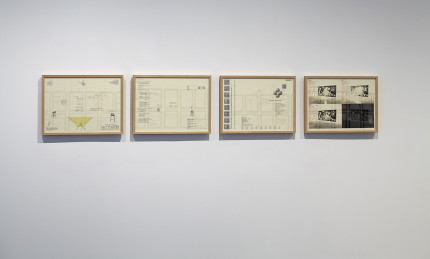

Guernica. The Art Gallery Problem: Watch and Enlighten, 2014

In 1973 the mathematician Victor Klee posed the following question: How many guards are necessary, and how many are sufficient, to patrol the paintings and works of art in an art gallery with n walls? This question of combinatorial geometry came to concern scientists in the following decades and is the topic of numerous papers. The six drawings in this installation are speculative examples of the “Art Gallery Problem,” as the question has come to be known. Besides its obvious reference to the theme of visibility, witnessing, and (the impossibility of ) having an overview in Guernica, the drawings also suggest that the logic and rationales informing the contemporary surveillance society have invaded the conception of the gallery space. Not just the artworks but those who look at the artworks are being watched. In other words, The Art Gallery Problem: Watch and Enlighten reframes Klee’s intriguing and seemingly innocent mathematical question as a question of contested politics.

[The art gallery problem or museum problem is a well-studied visibility problem in computational geometry. It originates from a real-world problem of guarding an art gallery with the minimum number of guards who together can observe the whole gallery. In the computational geometry version of the problem the layout of the art gallery is represented by a simple polygon and each guard is represented by a point in the polygon. A set  of points is said to guard a polygon if, for every point

of points is said to guard a polygon if, for every point  in the polygon, there is some

in the polygon, there is some  such that the line segment between

such that the line segment between  and

and  does not leave the polygon.]

does not leave the polygon.]

English

English

Guernica. Carpet Bombing, 2012

One of the iconic figures in Guernica is the lightbulb that oversees

the scenario and provides the only light in the otherwise dark space.

Installed in the gallery space is an enlarged real-life version of that

bulb. Next to it is a ladder that seemingly can be used if the bulb

needs to be replaced. The meaning of the bulb has been interpreted

several ways. One interpretation sees it as a man-made eternal sun

or the light of reason, while another points out that in Spanish the

word for lightbulb is bombilla, which is similar to bomba, the Spanish

word for bomb. Taking its cue from the latter interpretation, the

installation also includes a large-scale projection of footage of socalled

carpet bombings, a tactic that was introduced in the attack

on Guernica and later became common in warfare. For example,

German and British forces each used carpet bombing during World

War II, and the Americans relied on it during the Vietnam War.

However, in the context of the installation, the oversize bulb serves

the additional symbolic function of throwing continuous light on the

bombing footage, making sure that this horrific chapter in twentiethcentury

warfare is never forgotten.

English

English

Guernica. Spanish Pavilion 1937, 2014

Over the past year Daniel G. Andújar has stolen one million email

addresses on the Internet. During the exhibition he will send the

same message to each of the addresses at a rate calculated to finish

the project by the end of the exhibition. Visitors to the exhibition

can follow the sending of the email on a small monitor in the

gallery space. The email message contains a private (i.e., unofficial)

photograph of the Spanish pavilion at the 1937 World’s Fair. Only a

few official photographs of the pavilion exist, and the private photograph

included in the email is not one of them. Andújar purchased

the photograph on eBay and then cropped the image to show only the

pavilion, thus making it his own work. By distributing this image,

he enables the global public to “visit” the pavilion and reflect on the

message of Guernica.

Guernica. 1/1.000.000 Spanish Pavilion 1937, 2014

English

English

Guernica. Nichteinmischungsausschuss, 2012

Theword Nichteinmischungsausschuss—German for the international

Non-intervention Committee that was set up in 1936 to prevent personnel

and material from reaching the parties involved in the Spanish

Civil War—is written in large graffiti-like letters on one of the walls

in the gallery space. Joachim von Ribbentrop, the German representative

at the committee’s first meeting, would later write in his

memoirs, “It would have been better to call this the Intervention

Committee, for the whole activity of its members consisted in explaining

or concealing the participation of their countries in Spain.”

One of the most dreadful examples of this intervention was German

support for the carpet-bombing of the town of Guernica.

English

English

Guernica. Picasso Communist, 2012

Recently, the U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) declassified

the files it once maintained on Pablo Picasso. The files on display

in the exhibition show how the agency, concerned about Picasso’s

communist affiliations, followed the artist when he lived in Paris.

The declassification is only partial. Large parts of the information

are covered in black. Making sense of it all is more or less impossible.

The unredacted portions read as an “alternative” history of

Picasso as a political artist. Like art historians proper, the FBI gives

a detailed account of Picasso’s activities as well as his art. The account

includes a summary of an article published in connection with

an exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1957.

According to the files, the article, from the communist magazine The

Worker, argues that “PICASSO cannot be understood unless his life

in art and his life in politics are seen as a synthesis of his guiding

philosophy and social outlook.” From an oppositional political perspective

the FBI (likely unaware of the irony) seems to have taken a

similar approach in its investigation of Picasso.

English

English

Guernica. CCTV Guernica, 2014

An animated video shows odd characters looking at Guernica: Superman,

Marcel Duchamp’s iconic urinal, and the coyote from Joseph

Beuys’s I Like America and America Likes Me (1974). What the characters

have in common is that they, like the painting, belong to a

cultural narrative of courageous actions. The animated sequences are

interspersed with footage from the actual room in the Museo Reina

Sofía where Guernica is currently on display. The footage shows how

the painting is constantly guarded by two persons and thus points

out its need for protection as an invaluable artwork. Commenting on

this situation, another animated video features a soldier in front of

Guernica. He is dressed in combat uniform and carries an automatic

rifle. He closely inspects the painting as if it is an object of military

importance (which, metaphorically speaking, it is) before leaving the

exhibition space. The two videos thus dramatize the double status of

Guernica as an artifact inscribed in the mythology of art and fiction

and as a testament to an actual act of war.

English

English

Guernica. Universal Exhibition Paris 1937, 2012-2014

When the Spanish pavilion presented Pablo Picasso’s newly finished

painting Guernica (1937) at the World’s Fair in 1937 in Paris, not many

visitors stopped to look at its nightmarish depiction of the ongoing

Spanish Civil War. Instead, interest gathered around the German

and Russian pavilions and their Nazi and Communist propaganda.

Today, these political ideologies are well known to have been directly

involved in the atrocious destruction that the painting represents,

and Guernica itself has become one of the most popular artworks

in the world, canonized as a seminal statement of the dangers of

political ideology. Guernica 1937 is a discussion of the painting, the

World’s Fair, and their political-historical contexts. Through documentary

material presented in several vitrines and a projection of

footage related to the fair, the installation invites the audience to

openly and critically revisit the event. The installation addresses the

specific case of Guernica but also encourages reflection on the more

general question of how the reception of works of art is mediated

and framed by external circumstances. Moreover, the installation

reminds the audience of the violence that political propaganda all

too often seductively disguises and of the importance art—for example,

Guernica—can play in exposing this violence.

3D

3D

Beat the Whites with the Red Wedge, 2014

Golpead a los blancos con la cuña roja, 2014

Impresión sobre papel

42 x 59,4 cm

Arquitecturas, 2014

32 impresiones sobre papel

33 x 48,3 cm c/u

Liberator, 2014

Impresiones 3D en plástico PLA

180 piezas en rojo, blanco y negro

Medidas variables

Golpead a los blancos con la cuña roja, 2014

Impresión sobre papel

42 x 59,4 cm

Arquitecturas, 2014

32 impresiones sobre papel

33 x 48,3 cm c/u

Liberator, 2014

Impresiones 3D en plástico PLA

180 piezas en rojo, blanco y negro

Medidas variables

In 1919 El Lissitzky created Beat the Whites with the Red Wedge. With this poster he sought to promote a form of political action using the basic forms of suprematism, the revolutionary avant-garde movement of which he was a part. In opposition to his mentor, Kazimir Malevich, who strove for a higher, immaterial reality, El Lissitzky wanted to apply suprematism to the reality of the streets. Beat the Whites with the Red Wedge is a contemporary realization of this call to arms. On display in two vitrines are the components of four Liberator guns, one of the first all-plastic “printable” pistols developed and promoted by the Texas-based nonprofit, peer-sponsored organization Defense Distributed in 2013. The components were produced using (illegal) open-source data found on the Internet and a regular 3-D printer. Each component is white, red, or black. A reproduction of El Lissitzky’s original poster is placed on the wall, thus allowing an open comparison between two abstract ideas of “liberation” and concrete objects across time, space, politics, and technologies.

The Liberator was the culmination of the Wiki Weapon Project dedicated to exploring the new possibilities that 3-D technology offered those who claim the right to bear arms as stated in the 2nd Amendment of the U.S. Constitution. Seen from that perspective, the pistol is a radical invention. The Liberator is cheap and simple to produce and also bypasses existing gun laws. A print of the Liberator is without a serial number and does not demand registration, which is why the U.S. State Department has labeled them “ghost guns.” No one knows they exist. Despite an ongoing conflict with the State Department, Defense Distributed has continued to develop so-called printable firearms, and their products now include data for printing an automatic rifle.

Installation

Installation

Armed Citizen, 1998-2006

Questions of access are central to notions of the Internet as a new

space of freedom. The Chinese government is criticized when it blocks

certain websites, and the Internet is globally celebrated when activists

in the Middle East share their videos via social platforms like

Facebook. Most people will probably agree that accessing material

goods through online shopping is not only cheaper but easier than

going to the shopping mall. Armed Citizen is a series of images of one

hundred handguns that can be bought online like the millions of

other consumer goods the Internet has to offer. The images provide

no information about the guns, their type, price, or where they can be

bought. They simply present one gun after another as objects of desire

made available by the new economy of digitalized networked transactions.

The “armed citizens” that the title of the work refers to are,

regardless of why they buy the guns, the products of the commercial

logic embedded in contemporary access culture. The work furthermore

reflects a general loosening of the restrictions of gun control,

which most tragically has manifested itself in the many school shootings

in both Europe and the United States. The main argument for

more lenient gun laws is the need for personal protection, yet again

and again we are confronted with evidence that this object of security

primarily leads to an increase in violence and death.